The automotive industry increasingly agrees that electric propulsion is the future of land transportation. However, as e-mobility resurfaces—a concept familiar since the earliest days when internal combustion engines (ICE) and electric cars coexisted—a key debate arises: how should electric motors be powered? The common approach today is onboard battery packs, but an alternative technology gaining attention is hydrogen fuel cells.

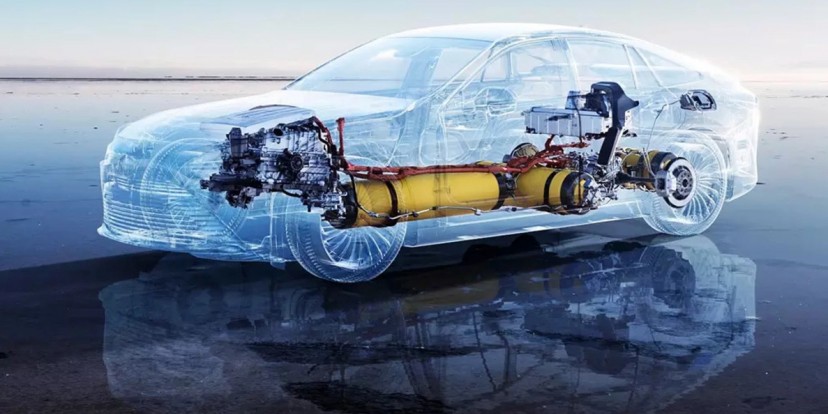

Honda Clarity Fuel Cell Vehicle

Honda Clarity Fuel Cell VehicleWhat Is a Fuel Cell?

Given the limited energy density of current battery technologies, some have proposed producing electricity onboard without the need for heavy, bulky batteries. This concept isn’t new; NASA utilized fuel cells in the 1960s on Gemini and Apollo missions to the moon. Among various types, proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs) dominate automotive applications.

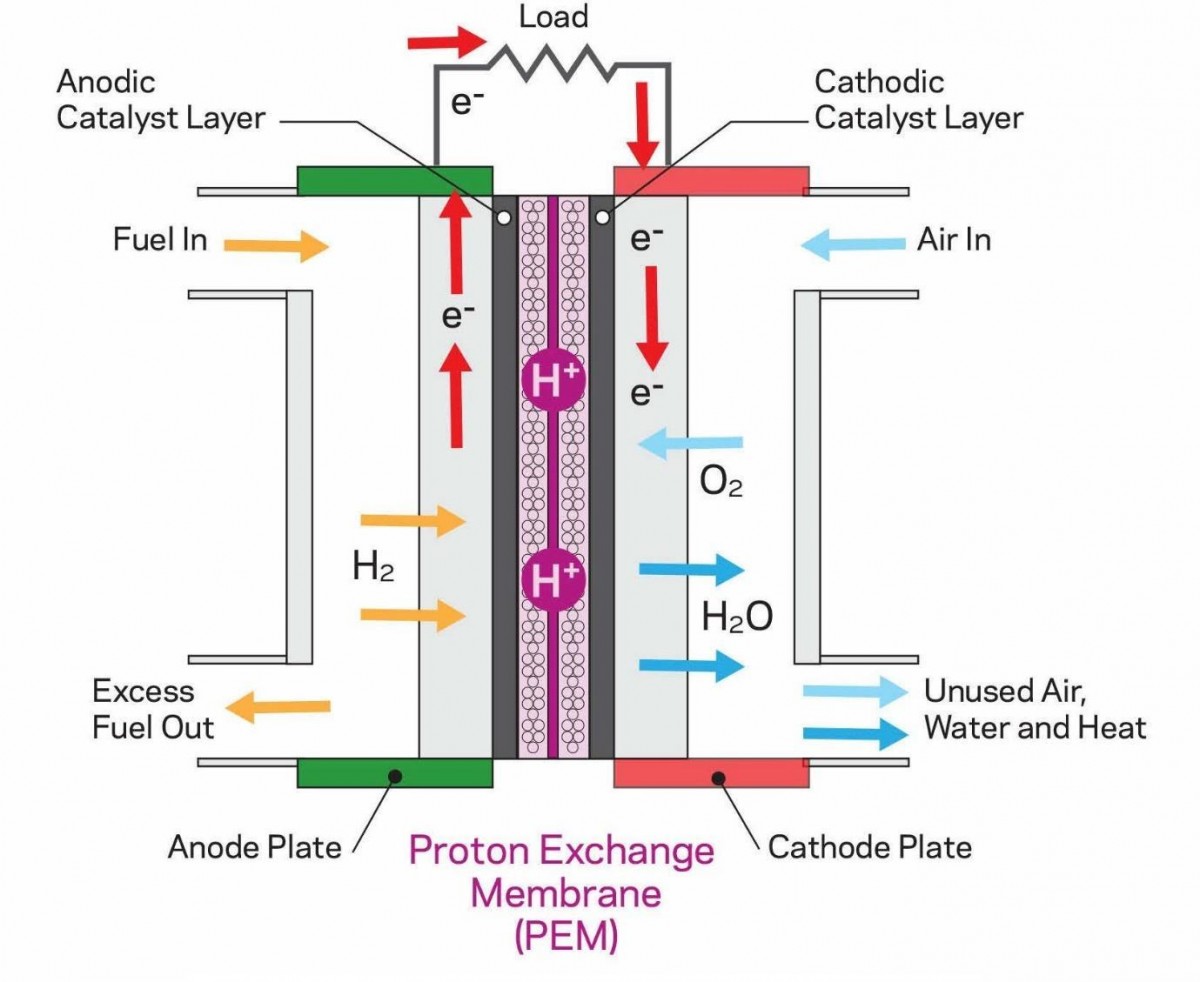

Fuel cells generate electricity through a simple process involving three components: the anode, cathode, and separator. Hydrogen gas (H2) is supplied to the anode, where it splits into protons and electrons. Positively charged protons pass through the separator, while electrons travel via an external circuit, creating an electric current.

At the cathode, atmospheric oxygen meets the protons and electrons to form water, which is expelled as the only emission—essentially a tailpipe you could drink from!

Nafion proton exchange membrane fuel cell

Nafion proton exchange membrane fuel cellHydrogen Production Methods

Hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe, does not exist freely on Earth and must be produced. Currently, there are three primary production methods plus an emerging fourth:

Gray hydrogen is produced by steam reforming natural gas, where natural gas reacts with heated steam to generate hydrogen and carbon dioxide, making it environmentally unfriendly.

Blue hydrogen follows the same process but incorporates carbon capture and storage technologies to prevent CO2 emissions from entering the atmosphere.

Green hydrogen is created via electrolysis, using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. This method is sustainable only if the electricity comes from renewable sources like wind or solar.

The turquoise hydrogen method—still in development—involves passing natural gas through molten metal to produce hydrogen and solid carbon, showing promise for future use.

Hydrogen production through sustainable electrolysis

Hydrogen production through sustainable electrolysisHydrogen Storage: Gas vs. Liquid

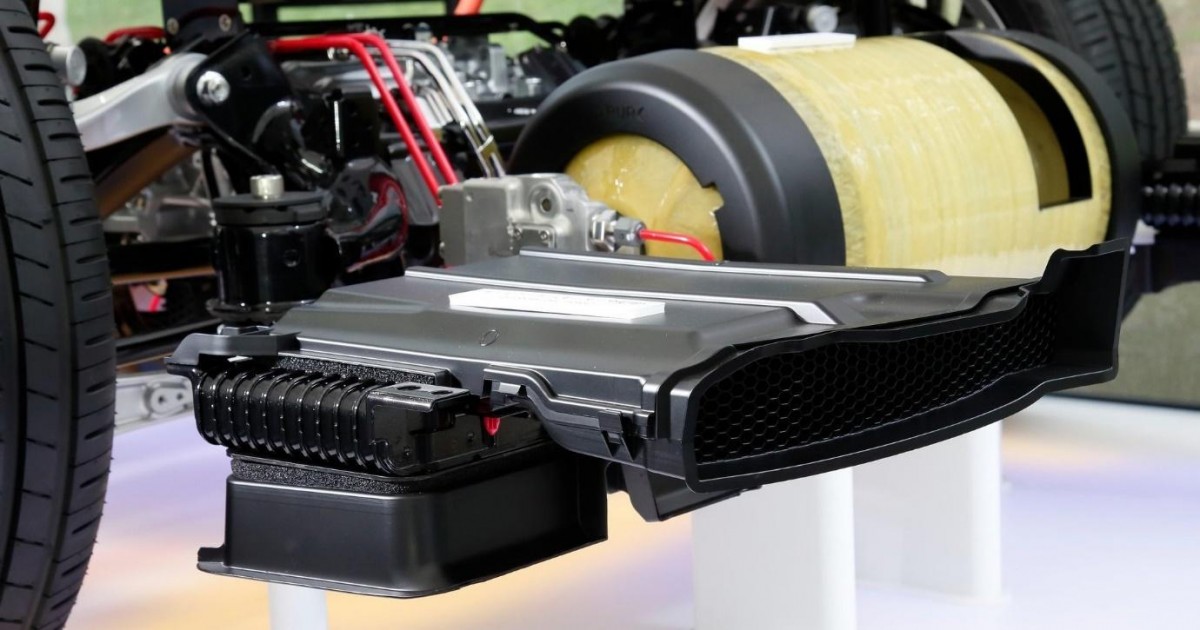

Hydrogen can be stored in gaseous or liquid states, each with pros and cons. As the lightest element, hydrogen requires high compression—currently about 700 bars—to be stored as gas, necessitating specialized, costly tanks.

Alternatively, hydrogen can be liquefied, which requires cooling to around -253°C, just 20 degrees above absolute zero. Both compression and liquefaction require substantial energy input.

Despite these challenges, hydrogen’s energy density is remarkable: 1 kg of hydrogen carries 33.3 kWh of energy, roughly 167 times more per kilogram than the best advanced battery packs.

Toyota Mirai’s gaseous H2 tanks are made from polyamide and carbon fiber

Toyota Mirai’s gaseous H2 tanks are made from polyamide and carbon fiberBatteries vs. Hydrogen Fuel Cells

Which is better: carrying stored electricity or producing it onboard? Currently, the automotive industry favors battery packs for several reasons.

PEMFC efficiency stands at about 60%. Steam reforming natural gas is 70% efficient, while electrolysis achieves approximately 75%. Hydrogen compression efficiency is around 89%, and liquefaction about 66%. The following table summarizes efficiency losses through various stages, comparing the most efficient hydrogen pathways with battery packs.

| Efficiency Comparison | Hydrogen | Battery Pack |

|---|---|---|

| Electrolysis (%) | 75 | - |

| Hydrogen Compression (%) | 89 | - |

| Fuel/Grid Transport (%) | 80 | 93 |

| Fuel Cell (%) | 60 | 94 |

| Permanent Magnet Motor (%) | 94 | 94 |

| DC/AC Conversion (%) | 93 | 93 |

| Charging (%) | - | 94 |

| Transmission (%) | 95 | 95 |

| Total Efficiency (%) | 27 | 73 |

The data shows that fuel cell vehicles currently operate with an efficiency comparable to petrol ICE cars. Given this, fuel cells are less viable for passenger vehicles today, explaining the industry’s preference for battery packs despite their limitations.

Moreover, hydrogen refueling costs are approximately 7 to 8 times higher than recharging an electric vehicle at home for equivalent distances. However, hydrogen’s high energy density could make it suitable for heavy trucks—provided sustainable hydrogen production methods become widely available.